« Back to AP Physics Guide / AP Physics 1 – Unit 3: Circular Motion

AP Physics 1 – Uniform Circular Motion: Centripetal Force, Banked Curves & Vertical Circles

1. Uniform Circular Motion: Velocity vs. Acceleration

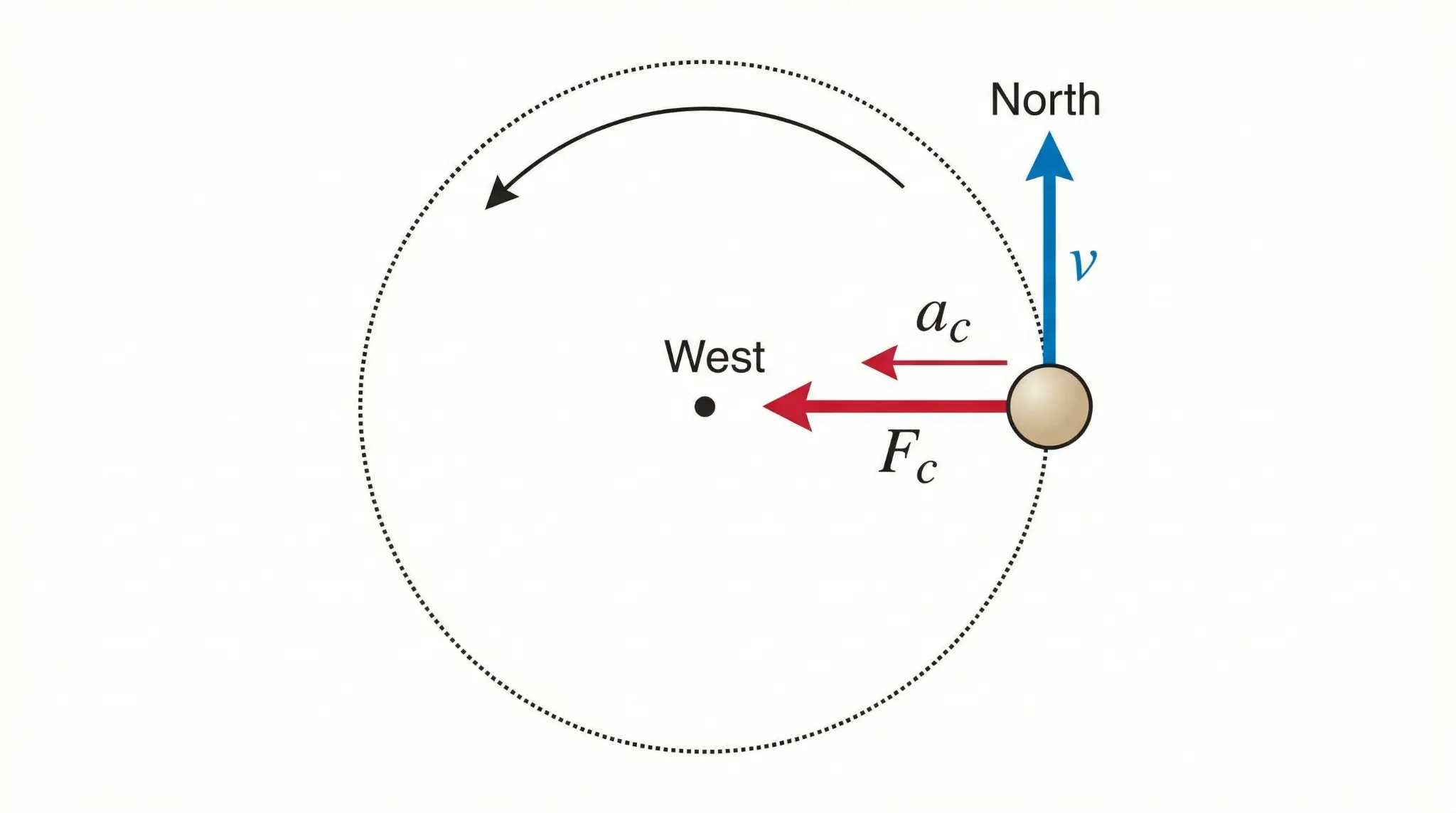

In uniform circular motion, the speed is constant, but the velocity keeps changing because its direction continuously changes toward the tangent of the circle. This changing direction is what creates a non‑zero acceleration even when the speed stays the same.

Always points toward the center of the circle.

![]()

The net inward force required to produce ![]() .

.

![]()

1.1 For the Nerds: Deriving

Here is a quick geometric proof using similar triangles.

and radius

and radius  is similar to the triangle for

is similar to the triangle for  and

and  .

.

The geometry gives the ratio

![]()

Divide both sides by ![]() :

:

![]()

Since ![]() and

and ![]() , we obtain

, we obtain

![]()

1.2 Period, Frequency & Speed on a Circle

In many AP Physics 1 circular‑motion problems, it is easier to think in terms of how long one revolution takes instead of just meters per second.

Time for one full revolution (seconds).

![]()

Revolutions per second (Hz).

![]()

Speed in a circle:

If one revolution travels a distance ![]() in time

in time ![]() , then

, then

![]()

2. Flat Curve: The “Car on a Curve” Problem

When a car turns a corner on level ground, the steering wheel only changes direction; the actual inward force is provided by static friction between the tires and the road. If friction disappears (ice), the car slides straight because no force points toward the center.

How to Solve Flat‑Curve Problems

Set the friction force equal to the required centripetal force:

![]()

![]()

(From Unit 2: on flat ground, ![]() , so

, so ![]()

2.5 Banked Turns (No Friction)

A classic AP Physics 1 question: “A car drives on a banked track. At what speed can it travel without relying on friction?” This has the same math as a conical pendulum.

The key is to resolve the Normal Force into vertical and horizontal components.

supplies the centripetal force toward the center of the curve.

supplies the centripetal force toward the center of the curve.

- Vertical (y):

(balances gravity)

(balances gravity) - Horizontal (x):

(provides centripetal force)

(provides centripetal force)

Divide the x‑equation by the y‑equation; mass and ![]() cancel:

cancel:

![]()

2.6 Conical Pendulum

A small mass whirling in a horizontal circle on a string (the “flying pig”) looks scary but is mathematically identical to the banked‑curve problem.

; the components work out the same way.

; the components work out the same way.

Break Tension into components:

- Vertical:

(balances gravity)

(balances gravity) - Horizontal:

(provides

(provides  )

)

Dividing gives the same result: ![]() .

.

2.7 Banked Turn with Friction

Real roads have friction, which creates a range of safe speeds rather than just one speed. The direction of friction depends on whether the car tends to slide up or down the slope.

Car tends to slide OUT; friction points down the slope.

![]()

Car tends to slide IN; friction points up the slope.

![]()

3. Vertical Circles (Loops & Roller Coasters)

Vertical‑circle problems are harder because gravity can help or oppose the inward direction depending on where the object is on the path. Remember: centripetal force is always the sum of forces toward the center.

Top of the Loop

Both Gravity and Normal Force point inward (toward the center).

![]()

Bottom of the Loop

Normal Force points inward (up), Gravity points outward (down).

![]()

Critical Speeds for a Loop‑the‑Loop

-

1. Minimum speed at the top:

Just enough to keep contact ( ):

):

-

2. Minimum speed at the bottom:

Using energy to get from bottom to top gives

(Derivation connects with conservation of energy in Unit 4.)

4. AP Physics 1 Circular Motion Practice Problems

Concept Check (MCQ Style)

Q1: A ball is swung in a horizontal circle of radius ![]() with speed

with speed ![]() . If the speed is doubled to

. If the speed is doubled to ![]() and radius stays the same, how does the required centripetal force change?

and radius stays the same, how does the required centripetal force change?

Click to see answer

Answer: It becomes four times larger.

Since ![]() , doubling

, doubling ![]() gives

gives ![]() , so the force is

, so the force is ![]() .

.

Tip: This uses proportional reasoning from the kinematics equation sheet.

Mini‑FRQ: Car Over a Hill

Scenario: A 1000 kg car drives over the top of a hill that has a circular cross‑section with radius ![]() .

.

(a) Derive an expression for the maximum speed ![]() the car can have without losing contact with the road.

the car can have without losing contact with the road.

(b) Calculate this speed.

Check solution

Part (a): At the top, inward direction is downward. Gravity is inward, Normal Force is outward.

![]() .

.

At the point of losing contact, ![]() , so

, so ![]() .

.

Thus ![]() .

.

Part (b): ![]() .

.

More Practice Problems

Flying Pig (Conical Pendulum): A toy plane on a string makes a horizontal circle. The string length is ![]() and makes an angle of

and makes an angle of ![]() with the vertical. Calculate its speed.

with the vertical. Calculate its speed.

See solution

Radius: ![]() .

.

Use ![]() .

.

![]() .

.

Vertical Loop Tension: A 2.0 kg bucket of water moves in a vertical circle of radius ![]() at speed

at speed ![]() . Find the tension at the bottom.

. Find the tension at the bottom.

See solution

At bottom: ![]() .

.

![]() .

.

Friction on a Flat Curve: A car rounds a flat curve of radius ![]() . If

. If ![]() , what is the maximum safe speed?

, what is the maximum safe speed?

See solution

Use ![]() .

.

![]() .

.

What’s Next in Unit 3?

Now that you’ve mastered circular motion on Earth, move into “space physics” with gravity and orbits.

- 🪐 Next Lesson: Universal Gravitation (The Force) »

- 🔁 Review: AP Physics 1 – Newton’s Laws (Unit 2)

- 📚 Go back: AP Physics Guide (AP Physics 1, 2 & C)